(Objective 16-3) The following are common tests of details of balances for the audit of accounts receivable:

1. Obtain a list of aged accounts receivable, foot the list, and trace the total to the general ledger.

2. Trace 35 accounts to the accounts receivable master file for name, amount, and age categories.

3. Examine and document cash receipts on accounts receivable for 20 days after the engagement date. 4. Request 25 positive and 65 negative confirmations of accounts receivable.

5. Perform alternative procedures on accounts not responding to second requests by examining subsequent cash receipts documentation and shipping reports or sales invoices.

6. Test the sales cutoff by tracing entries in the sales journal for 15 days before and after the balance sheet date to shipping documents, if available, and/or sales invoices.

7. Determine whether any accounts receivable have been pledged, discounted, sold, assigned, or guaranteed by others. 8. Evaluate the materiality of credit balances in the aged trial balance.

Required

For each audit procedure, identify the balance-related audit objective or objectives it partially or fully satisfies.

(Objective 16-3)

DESIGNING TESTS OF DETAILS OF BALANCES

Even though auditors emphasize balance sheet accounts in tests of details of balances, they are not ignoring income statement accounts because the income statement accounts are tested as a by-product of the balance sheet tests. For example, if the auditor confirms accounts receivable balances and finds overstatements caused by mistakes in billing customers, then both accounts receivable and sales are overstated. Confirmation of accounts receivable is the most important test of details of accounts receivable. We will discuss confirmation briefly as we study the appropriate tests for each of the balance-related audit objectives. We’ll examine it in more detail later in this chapter. For our discussion of tests of details of balances for accounts receivable, we will focus on balance-related audit objectives. We will also assume two things:

1. Auditors have completed an evidence planning worksheet similar to the one in Figure 16-7.

2. They have decided planned detection risk for tests of details for each balancerelated audit objective. The audit procedures selected and their sample size will depend heavily on whether planned evidence for a given objective is low, medium, or high.

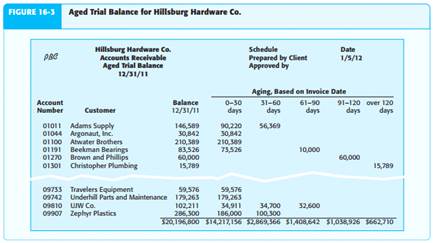

Most tests of accounts receivable and the allowance for uncollectible accounts are based on the aged trial balance. An aged trial balance lists the balances in the accounts receivable master file at the balance sheet date, including individual customer balances outstanding and a breakdown of each balance by the time passed between the date of sale and the balance sheet date. Figure 16-3 illustrates a typical aged trial balance, based on the Hillsburg Hardware example. Notice that the total is the same as accounts receivable on the general ledger trial balance on page 150. Ordinarily, auditors test the information on the aged trial balance for detail tie-in before any other tests to verify that the population being tested agrees with the general ledger and accounts receivable master file. The total column and the columns depicting the aging must be test footed and the total on the trial balance compared with the general ledger. In addition, auditors should trace a sample of individual balances to supporting documents such as duplicate sales invoices to verify the customer’s name, balance, and proper aging. The extent of the testing for detail tie-in depends on the number of accounts involved, the degree to which the master file has been tested as a part of tests of controls and substantive tests of transactions, and the extent to which the schedule has been verified by an internal auditor or other independent person

before it is given to the auditor. Auditors often use audit software to foot and cross-foot the aged trial balance and to recalculate the aging. Confirmation of customers’ balances is the most important test of details of balances for determining the existence of recorded accounts receivable. When customers do not respond to confirmations, auditors also examine supporting documents to verify the shipment of goods and evidence of subsequent cash receipts to determine whether the accounts were collected. Normally, auditors do not examine shipping documents or evidence of subsequent cash receipts for any account in the sample that is confirmed, but they may use these documents extensively as alternative evidence for nonresponses. It is difficult for auditors to test for account balances omitted from the aged trial balance except by relying on the self-balancing nature of the accounts receivable master file. For example, if the client accidentally excluded an account receivable from the trial balance, the only likely way it will be discovered is for the auditor to foot the accounts receivable trial balance and reconcile the balance with the control account in the general ledger. If all sales to a customer are omitted from the sales journal, the understatement of accounts receivable is almost impossible to uncover by tests of details of balances. For example, auditors rarely send accounts receivable confirmations to customers with zero balances, in part because research shows that customers are unlikely to respond to requests that indicate their balances are understated. In addition, unrecorded sales to a new customer are difficult to identify for confirmation because that customer is not included in the accounts receivable master file. The understatement of sales and accounts receivable is best uncovered by substantive tests of transactions for shipments made but not recorded (completeness objective for tests of sales transactions) and by analytical procedures. Confirmation of accounts selected from the trial balance is the most common test of details of balances for the accuracy of accounts receivable. When customers do not respond to confirmation requests, auditors examine supporting documents in the same way as described for the existence objective. Auditors perform tests of the debits and credits to individual customers’ balances by examining supporting documentation for shipments and cash receipts. Normally, auditors can evaluate the classification of accounts receivable relatively easily, by reviewing the aged trial balance for material receivables from affiliates, officers, directors, or other related parties. Auditors should verify that notes receivable or accounts that should be classified as noncurrent assets are separated from regular accounts, and significant credit balances in accounts receivable are reclassified as accounts payable. There is a close relationship between the classification balance-related objective and the related classification and understandability presentation and disclosure objective. To satisfy the classification balance-related audit objective, the auditor must determine whether the client has correctly separated different classifications of accounts receivable. For example, the auditor will determine whether receivables from related parties have been separated on the aged trial balance. To satisfy the objective for presentation and disclosure, the auditor must make sure that the classifications are properly presented by determining whether related party transactions are correctly shown in the financial statements during the completion phase of the audit. Cutoff misstatements exist when current period transactions are recorded in the subsequent period or vice versa. The objective of cutoff tests, regardless of the type of transaction, is to verify whether transactions near the end of the accounting period are recorded in the proper period. The cutoff objective is one of the most important in the cycle because misstatements in cutoff can significantly affect current period income. For example, the intentional or unintentional inclusion of several large, subsequent period sales in the current period—or the exclusion of several current period sales returns and allowances—can materially overstate net earnings. Cutoff misstatements can occur for sales, sales returns and allowances, and cash receipts. For each one, auditors require a threefold approach to determine the reasonableness of cutoff:

1. Decide on the appropriate criteria for cutoff.

2. Evaluate whether the client has established adequate procedures to ensure a reasonable cutoff.

3. Test whether the cutoff was correct.

Sales Cutoff Most merchandising and manufacturing clients record a sale based on shipment of goods criterion. However, some companies record invoices at the time title passes, which can occur before shipment (as in the case of custom-manufactured goods), at the time of shipment, or subsequent to shipment. For the correct measure – ment of current period income, the method must be in accordance with accounting standards and consistently applied. The most important part of evaluating the client’s method of obtaining a reliable cutoff is to determine the procedures in use. When a client issues prenumbered shipping documents sequentially, it is usually a simple matter to evaluate and test cutoff. Moreover, the segregation of duties between the shipping and the billing function also enhances the likelihood of recording transactions in the proper period. However, if shipments are made by company truck, if the shipping records are unnumbered, and if shipping and billing department personnel are not independent of each other, it may be difficult, if not impossible, to be assured of an accurate cutoff. When the client’s internal controls are adequate, auditors can usually verify the cutoff by obtaining the shipping document number for the last shipment made at the end of the period and comparing this number with current and subsequent period recorded sales. As an illustration, assume the shipping document number for the last shipment in the current period is 1489. All recorded sales before the end of the period

should bear a shipping document number preceding number 1490, and no sales recorded and shipped in the subsequent period should have a bill of lading numbered 1489 or lower. An auditor can easily test this by comparing recorded sales with the related shipping documents for the last few days of the current period and the first few days of the subsequent period. Sales Returns and Allowances Cutoff Accounting standards require that sales returns and allowances be matched with related sales if the amounts are material. For example, if current period shipments are returned in the subsequent period, the sales return should appear in the current period. (The returned goods should be treated as current period inventory.) For most companies, however, sales returns and allowances are recorded in the accounting period in which they occur, under the assumption of approximately equal, offsetting amounts at the beginning and end of each accounting period. This approach is acceptable as long as the amounts are not material. Some companies establish a reserve, similar to the allowance for uncollectible accounts, for the expected amount of returns in the subsequent period. When the auditor is confident that the client records all sales returns and allow – ances promptly, the cutoff tests are simple and straightforward. The auditor can examine supporting documentation for a sample of sales returns and allowances recorded during several weeks subsequent to the closing date to determine the date of the original sale. If auditors discover that the amounts recorded in the subsequent period are significantly different from unrecorded returns and allowances at the beginning of the period under audit, they must consider an adjustment. For example, a company may experience an increase in sales returns when it launches a new product. In addition, if the internal controls for recording sales returns and allowances are evaluated as ineffective, a larger sample is needed to verify cutoff. Cash Receipts Cutoff For most audits, a proper cash receipts cutoff is less important than either the sales or the sales returns and allowances cutoff because the improper cutoff of cash affects only the cash and the accounts receivable balances, not earnings. Nevertheless, if the misstatement is material, it can affect the fair presentation of these accounts, especially when cash is a small or negative balance. It is easy to test for a cash receipts cutoff misstatement (often called holding the cash receipts book open) by tracing recorded cash receipts to subsequent period bank deposits on the bank statement. If a delay of several days exists, that could indicate a cutoff misstatement. To some degree, auditors may also rely on the confirmation of accounts receivable to uncover cutoff misstatements for sales, sales returns and allowances, and cash receipts. However, it is often difficult to distinguish a cutoff misstatement from a normal timing difference due to shipments and payments in transit at year end. For example, if a customer mails and records a check to a client for payment of an unpaid account on December 30 and the client receives and records the amount on January 2, the records of the two organizations will be different on December 31. This is not a cutoff misstatement, but a timing difference due to the delivery time. It may be difficult for the auditor to evaluate whether a cutoff misstatement or a timing difference occurred when a confirmation reply is the source of information. This type of situation requires additional investigation, such as inspection of supporting documents. Accounting standards require that companies state accounts receivable at the amount that will ultimately be collected. The realizable value of accounts receivable equals gross accounts receivable less the allowance for uncollectible accounts. To calculate the allowance, the client estimates the total amount of accounts receivable that it expects to be uncollectible. Obviously, clients cannot predict the future precisely, but it is necessary for the auditor to evaluate whether the client’s allowance is reasonable, considering all available facts. To assist with this evaluation, the auditor often prepares an audit schedule that analyzes the allowance for uncollectible accounts, as illustrated in Figure 16-4. In this example, the analysis indicates that the allowance is understated. This can be the result of the client failing to adjust the allowance or economic factors. Note that the potential understatement of the reserve was signaled by the analytical procedures in Table 16-3 (p. 525) for Hillsburg Hardware. To begin the evaluation of the allowance for uncollectible accounts, the auditor reviews the results of the tests of controls that are concerned with the client’s credit policy. If the client’s credit policy has remained unchanged and the results of the tests of credit policy and credit approval are consistent with those of the preceding year, the change in the balance in the allowance for uncollectible accounts should reflect only changes in economic conditions and sales volume. However, if the client’s credit policy or the degree to which it correctly functions has significantly changed, auditors must take great care to consider the effects of these changes as well. Auditors often evaluate the adequacy of the allowance by carefully examining the noncurrent accounts on the aged trial balance to determine which ones have not been paid subsequent to the balance sheet date. The size and age of unpaid balances can then be compared with similar information from previous years to evaluate whether the amount of noncurrent receivables is increasing or decreasing over time. Auditors also gain insights into the collectibility of the accounts by examining credit files, discussions with the credit manager, and review of the client’s correspondence file. These procedures are especially important if a few large balances are noncurrent and are not being paid on a regular basis. Auditors face two shortcomings in evaluating the allowance by reviewing individual noncurrent balances on the aged trial balance. First, the current accounts are ignored in establishing the adequacy of the allowance, even though some of these amounts will undoubtedly become uncollectible. Second, it is difficult to compare the results of the current year with those of previous years on such an unstructured basis. If the accounts are becoming progressively uncollectible over several years, this fact can be overlooked. To avoid these two shortcomings, clients can establish a history of bad debt write-offs over a period of time as a frame of reference for evaluating the current year’s allowance. For example, a client might calculate that 2 percent of current accounts, 10 percent of 30- to 90-day accounts, and 35 percent of all balances over 90 days ultimately become uncollectible. Auditors can apply these percentages to the current year’s aged trial balance totals and compare the result with the balance in the allowance account. Of course, the

Tags: Assignment Help for Students, Assignment Help Free, Assignment Help Online Free, Assignment Help Websites, assignmenthelp, AssignmentHelpOnline, BestAssignmentHelp, myassignmenthelp, OnlineAssignmentHelp, Student Assignment Help, University Assignment Help